Micol e Mahatsanga - Laboratorio Anacronistico - Foto di Valentina Casalini

Micol e Mahatsanga - Laboratorio Anacronistico - Foto di Valentina Casalini

Laboratorio Anacronistico

«Laboratorio Anacronistico» is a exhibition of the artists Micol Grazioli and Mahatsanga Le Dantec.

The exhibition is a part of "ArtCycle 2020", a program around humans, art and environment launched by Spazio PierA, a place of exchange and contemporary art in Trento (Italy).

The anachronistic laboratory is a place where time mixes, where we anticipate the present that postpones the future, where absurdities are current. It is a place for those who think that progress regrets the past, for those who want to become farmers, for those who don't have time, for those who wonder if we have got the wrong planet.

Because of the health situation, the exhibition was digitized by the artists, via a virtual platform (fr-it): https://www.spaziopieravirtuale.com/

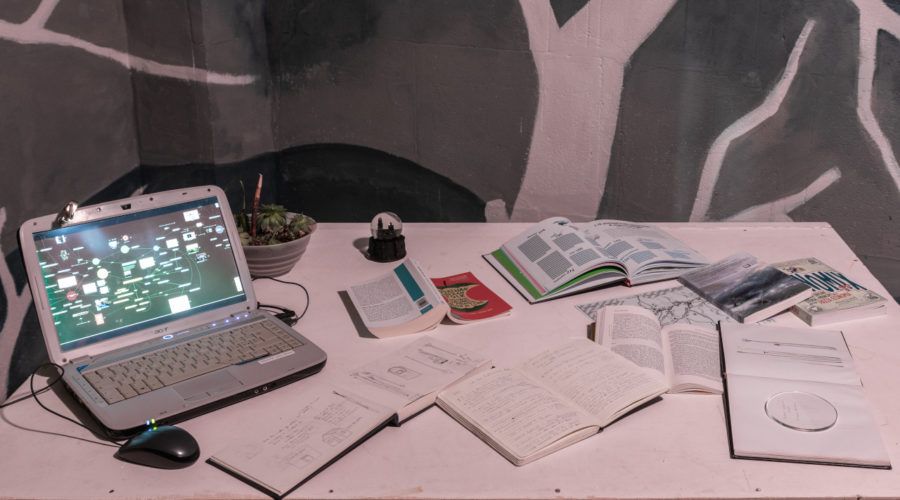

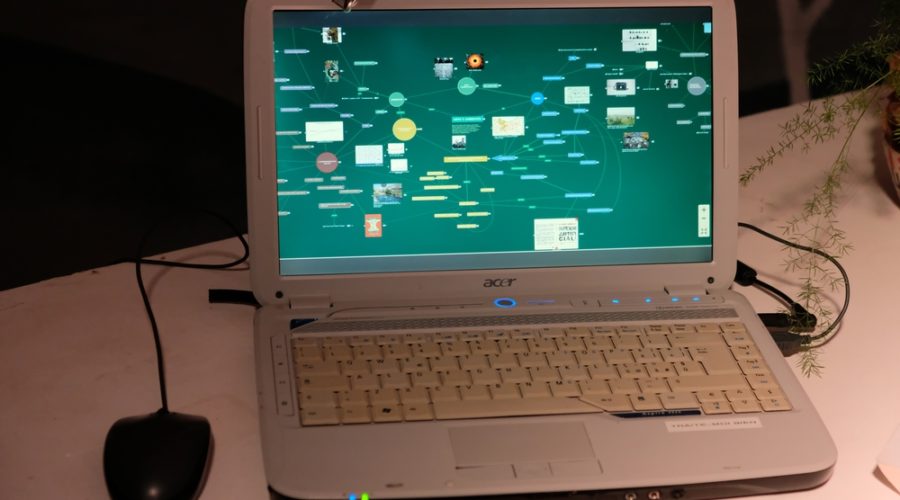

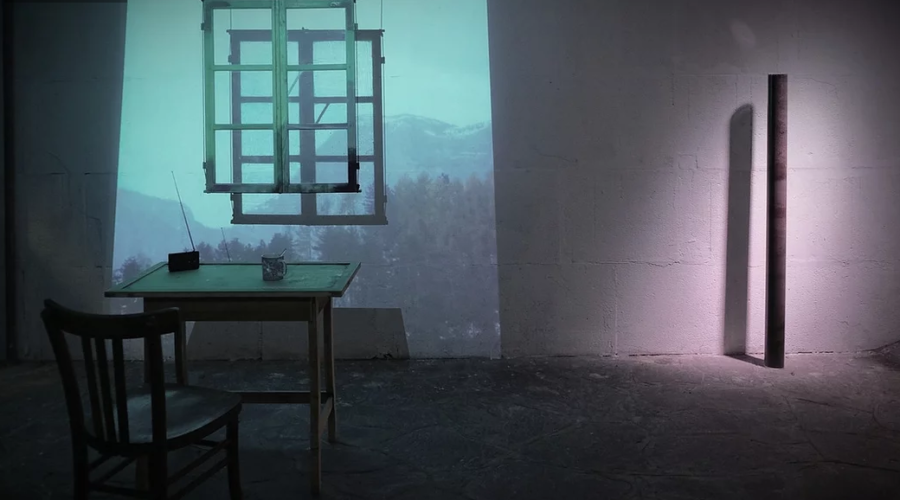

The interventions are "La Finestra", "Terra d'uomo" and "Reperto ICCD03 00109557". On a table it's possible to discover the research work of the two artists, through documentations and a conceptual map. The virtual platform inspired them also digital art creations.

Micol e Mahatsanga - Laboratorio Anacronistico - Foto di Valentina Casalini

Micol e Mahatsanga - Laboratorio Anacronistico - Foto di Valentina Casalini

Reperto ICCD03 00109557

Multilayer, screen, computer, spotlight, metal structure, glass, soil.

Micol Grazioli and Mahatsanga Le Dantec

Inside a laboratory machine—a black box elevated by a metal structure—indicator lights blink among electrical wires.

The soil lies beneath glass, dimly lit from behind. A farmer toils, a tiny hologram, repeatedly digging with a hoe.

A world in a box, scaled down and preserved by a technology both futuristic and obsolete.

The work was featured in an E-CRIT by the Collettivo Dialoghi Artistici:

https://collettivodialoghiartistici.it/portfolio-item/e-crit-6micol-grazioli/

Terra d’uomo

Core sample – Plexiglass, soil, peat, ceramic, charcoal, grass, organic waste

Micol Grazioli and Mahatsanga Le Dantec

Terra preta is one of the most fertile soils in the world. It is typical of the Amazon basin and—contrary to common assumptions—it is of anthropogenic origin, more precisely pre-Columbian.

Discoveries like this remind us that the Anthropocene is not only about human destruction, but also about possible symbiosis between humans and the environment.

We don’t simply adapt to the environment we live in—we modify it in order to inhabit it, just as plants did before us, creating conditions favorable to life.

Including our life, which is not as self-sufficient as we like to believe.

It would be madness to think we can dissociate from the planet and reshape it without consequences.

The Indigenous peoples who created terra preta, in collaboration with the forest, transformed their environment in order to live in it—but they did so while preserving its balance.

Today, we are studying the composition of terra preta, and perhaps we are learning a lesson: that instead of seeking solutions in hypothetical new technologies, we might find them in techniques that are 2,000 years old.